Selected Articles and Book Chapters

“Social Activism and Science Fiction.” New Routledge Companion to Science Fiction. Ed. Mark Bould, Andrew Boulton Sheryl Vint. London: Routledge, 2024.

This essay traces a genealogy of science fiction that ends with my beginning: Through their editing and the voices and stories they centre, brown and Imarisha put the relationships between activism and sf at the heart of Octavia’s Brood, thereby making the anthology a portal for many collective endeavours to change the world. Read it here.

“Collective Climate Action: Indigenous and Black Feminist Knowledge-Production, Speculative Science Stories, and Climate Change Literature.” Cambridge Companion to Literature and Climate. Ed. Adeline Putra-Johns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Some of the most vital contributions to recent climate change literature come not in the form of cli-fi but in multi-form stories of speculative science written by Indigenous and Black women. These narratives defy boundaries among fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and theory as well as genre boundaries. They also trouble binaries of individual and collective action or individual authorship and collective voice by emphasizing relations with activist communities and kinship with the more-than-human world. Read it HERE.

“The Technology of the Short Story: From Sci-Fi to Cli-Fi.” Cambridge Companion to the American Short Story. Ed. Michael Collins and Gavin Jones. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

This essay shows how recent science fiction writers build on a long history to confront climate change and imagine the social effects of changes in science, technology, and nature. These efforts, which are shaped by relationships to editors, movements, and new forms of technology and collaboration, revitalize the genre and move it toward imagining and creating freer and more just worlds. Read it HERE.

“Imperialism.” Keywords for Gender and Sexuality Studies. Ed. The Keywords Feminist Editorial Collective. New York: NYU Press, 2021.

This essay explores why holding onto the “harsher” term imperialism has once again taken on special urgency for scholars of gender and sexuality as it often has, in times of war, state violence, militarism, and deepening international economic inequalities, in response to the leadership of anti- imperialist movements. READ IT HERE.

“Genre” in Keywords for Comics Studies. Ed. Fawaz, Streeby, and Whaley. New York: NYU Press, 2020.

In this essay I argue for the creative work of genre activated by different kinds of comics readers and viewers despite industrial constraints inside and outside the United States, across multiple platforms, including film, TV, games, and internet forms of digital comics. Read it here

“Climate Refugees in the Greenhouse World: Archiving Global Warming with Octavia E. Butler" from Imagining the Future of Climate Change: Worldmaking through Science Fiction and Activism (University of California Press, 2018). Read it here.

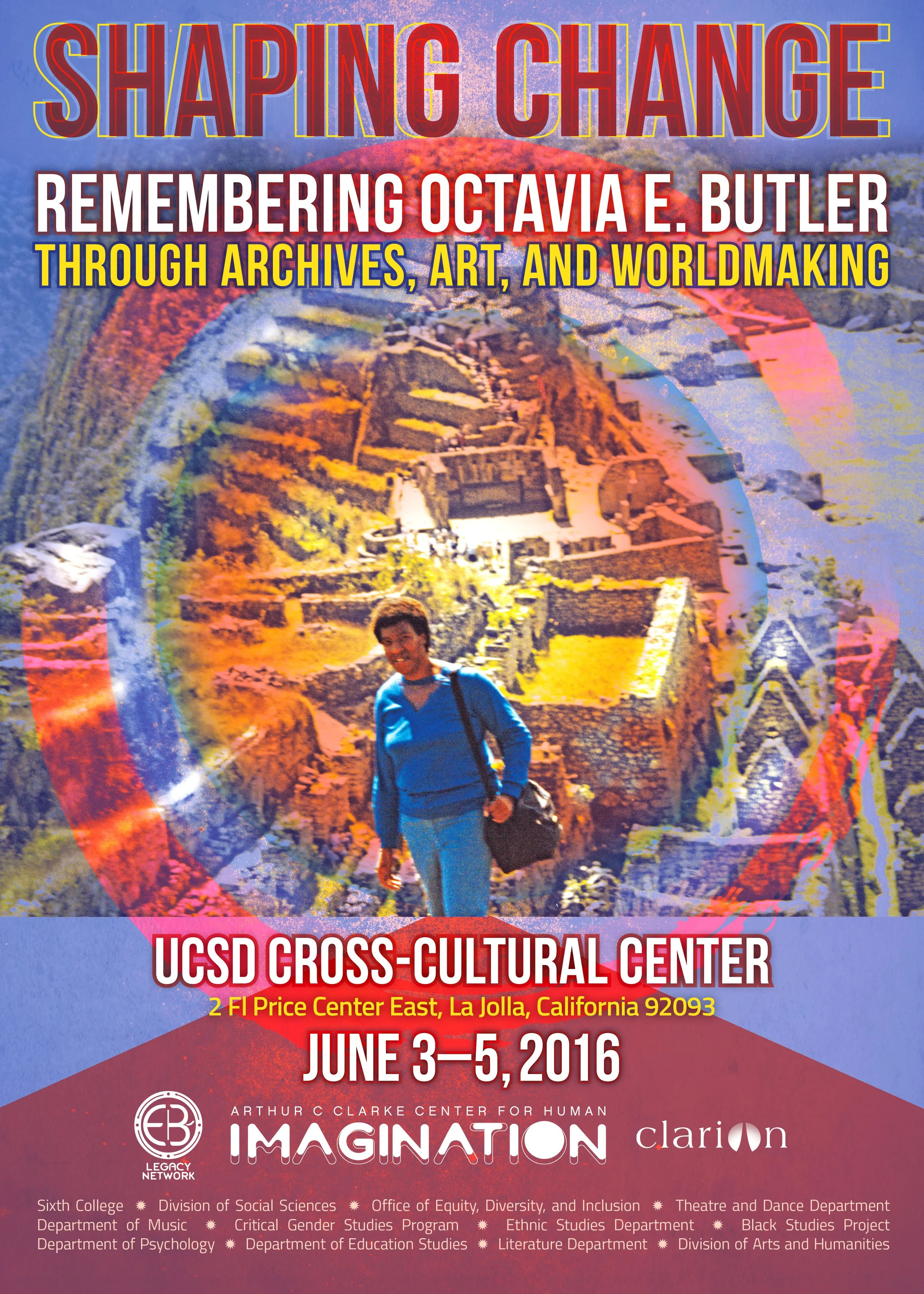

“Speculative Writing, Art, and World-Making in the Wake of Octavia E. Butler as Feminist Theory,” Feminist Studies 46:2 (20)

Read it here

Shelley Streeby (2018): Radical Reproduction: Octavia E. Butler’s HistoFuturist Archiving as Speculative Theory, Women's Studies, DOI: 10.1080/00497878.2018.1518619

Read it here. In this essay for a special issue of Women’s Studies co-edited by Moya Bailey and Ayana Jamieson, I argue that Butler’s massive archive at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California helps us see her significant contributions as a radical Black feminist theorist, historiographer, and researcher across fields and disciplines.

"Imagining Sensate Democracy: Beyond Republicanism, Liberalism, and the Literary" for American Literary History. Volume 30, Issue 2, (April 2018), 355–367.

This essay explores the significance of the body and bodies for theories of democracy in several recent books, especially Judith Butler’s Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. I suggest that Butler focuses on the body as connector across experiences of precarity as she speculates on “alliances that assemble across differences.” Read it here.

"Heroism and Comics Form: Feminist and Queer Speculations" for "Queer About Comics" Special Issue of American Literature, ed. Ramzi Fawaz and Darieck Scott, Forthcoming Spring 2018

"...One of my guiding premises is that queer studies and especially queer of color critique have much to offer comics studies. As Siobhan Somerville explains, “queer” since the 1980s functions both “as an umbrella term that refers to a range of sexual identities that are ‘not straight,’” and as an analytic that “calls into question the stability of any such categories of identity based on sexual orientation,” thereby exposing the latter as constructions that “establish and police the line between the ‘normal’ and the ‘abnormal.’ In addition, I build on queer of color analysis modeled by scholars such as Roderick Ferguson, Jose Munoz, and Fatima El-Tayeb, all of whom examine gender, race, sexuality, and nation as intertwining social constructions..." Read it here.

“Reading Jaime Hernandez’s Comics as Speculative Fiction.” Reprinted in Altermundos: Latin@ Speculative Literature, Film, and Popular Culture, edited Olguin and Merla-Watson. University of Washington Press. 2017.

"...By connecting the other side of the universe to Maggie’s apartment, the publishers called attention to a juxtaposition and convergence of sff and realist worlds that has characterized Jaime’s entire career, as I have suggested in this essay. It is at the heart of his speculative brilliance, as not only one of the greatest comics artists of all time but also as a major contributor to the Latina/o speculative arts. " Read it here.

“Speculative Fictions of A Divided World: Reading Octavia E. Butler in South Korea.” ELLAK Journal of English Language and Literature 62:2 (2016): 149-162.

Butler’s work anticipates and joins an emerging conversation about global inequalities, international and transnational divisions and connections, and climate change in recent science fiction and fantasy films in global mass culture. Some involve significant contributions by Korean cultural producers, most famously, The Host (2006) and Snowpiercer (2013), both directed by Bong Joon Ho.” Read it here.

"Doing Justice to the Archive: Beyond Literature," Unsettled States: Nineteenth-Century American Studies, ed. Dana Luciano and Ivy Wilson (New York: NYU Press, 2015).

"When Lucy Parsons worried that the Famous Speeches remained in the archives of history, almost forgotten, what kind of archives and history did she mean? Was she referring to the archives of the state, which classified the Haymarket anarchists as murderous criminals? Was her labor as a publisher part of an effort to push the men’s last words from the state’s juridical and punitive archive into another kind of archive where what happened might be remembered differently and where the past might cross back over into the present and the future rather than remaining safely encased in its containers? Should we call this archive literature, even though the gate-keeping guardians of the aesthetic, whose predictable jeremiads intermittently warn that only they are capable of analyzing form, have rarely included it within that category? What forms might these archives take other than literature?" Read it here.

Co-authored with Ben Balthaser, "Mass Culture, the Novel, and the American Left," The Oxford History of the Novel in English, Volume 6: The American Novel, 1870-1940 (London: Oxford University Press, 2014), ed. Michael Elliot and Priscilla Wald

This chapter explores the complex relationship between the left and mass culture in the first four decades of the twentieth century, and how writers and critics on the left understood mass culture's connection with the novel. It first considers the meanings of left, mass culture, and novel and why they belong together before turning to a discussion of literary realism in relation to emergent forms of mass media of the period. It then explains how novels participated in the cultures of sentiment and sensation and discusses the emergence of radical novels as well as the relationship between class and mass culture.

"Speculative Archives: Histories of the Future of Education," Pacific Coast Philology, Volume 49, Issue 1, 2014, pp. 25-40.

This essay explores the cultural history of UCSD and Southern California as places where speculative theorizing about utopia, dystopia, imagining the future, and reimagining the past has long been occurring. The first part is on Fredric Jameson’s and Kim Stanley Robinson’s theories of utopia and their relevance for the utopian project of public education; the second turns to alternate Afrofuturist worlds and Octavia Butler as an early theorist of neoliberalism; and the third focuses on speculative fictions of education, labor, technology, the future, and the idea of a radically networked enclave of resistance or social movement in the US/Mexico borderlands. Read it here.

"Empire," Keywords for American Cultural Studies, Second Edition (New York: NYU Press, 2014), ed. Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler

"For most of the twentieth century, the intellectual and political leaders of the United States denied that the nation was an empire. Then around 1994, things began to change, with the neoconservatives aligned with the Project for a New American Century (PNAC) openly embracing the idea of an American empire capable of ruling the post–Cold War world. This shift is a good example of the process Raymond Williams describes in Keywords (1976/1983, 11–26), whereby changes in the significance of words occur rapidly at times of crisis. For Williams, World War II decisively shaped the remarkable transformations in the meanings of certain keywords that inspired his book. In the twenty-first-century United States, the response of the Bush administration to 9/11, which sociologist Giovanni Arrighi calls “a case of great-power suicide” (2009, 82), precipitated a similar crisis..." Read it here.

“Cheap Sensation: Pamphlet Potboilers and Beadle’s Dime Novels.” The Oxford History Of The Novel in English: American Novels to 1870, Vol 5. Edited Gerald Kennedy and Leland Person. London: Oxford University Press, 2014.

This chapter focuses on the cheap sensational fiction written by authors such as George Lippard, Ned Buntline, and A. J. H. Duganne for story-papers in the late nineteenth century. More specifically, it examines the role played by Beadle and Company in popularizing cheap sensational literature during the period by publishing dime novels. The chapter cites some examples of dime novels of the period, including Lippard’s The Quaker City; or, The Monks of Monk Hall (1844–1845), E. D. E. N. Southworth’s The Hidden Hand; or, Capitola the Madcap (1859), Edward Wheeler’s Deadwood Dick, The Prince of the Road; or, The Black Rider of the Black Hills (1877), and Edward Ellis’s Seth Jones; or, The Captives of the Frontier (1860). It also considers mass-circulation story-papers such as the Flag of Our Union, the Star Spangled Banner, and Robert Bonner’s New York Ledger.

"Imagining Mexico in Love and War: Nineteenth- Century U.S. Literature and Visual Culture," Mexico and Mexicans in the Making of the United States. Ed. John Tutino. Houston: University of Texas Press, 2012: 110-140.

This chapter surveys the literary and cultural visions of Mexico produced in the US in response to three periods of military conflict in Mexico: first, the war against Spain that began in 18io and ended in 1821 with the emergence of Mexico as a nation; second, the Texas war for in dependence of 1835-1836 and the U. S.-Mexico War of 1846-1848, which together expanded U. S. national territory, diminished Mexico's, and radically transformed the relationships between the two nations; and, finally, the 1858-1861 War of Reform and the 1862-1867 French intervention in Mexico, a period of ongoing wars in Mexico that overlapped with the U.S. Civil War. Although it is sometimes suggested that during these years the US turned inward in response to its own national trauma, I argue that debates about national divisions, race, labor, property, govern ment, and empire were shaped by comparisons between the United States and Mexico in literature and culture.

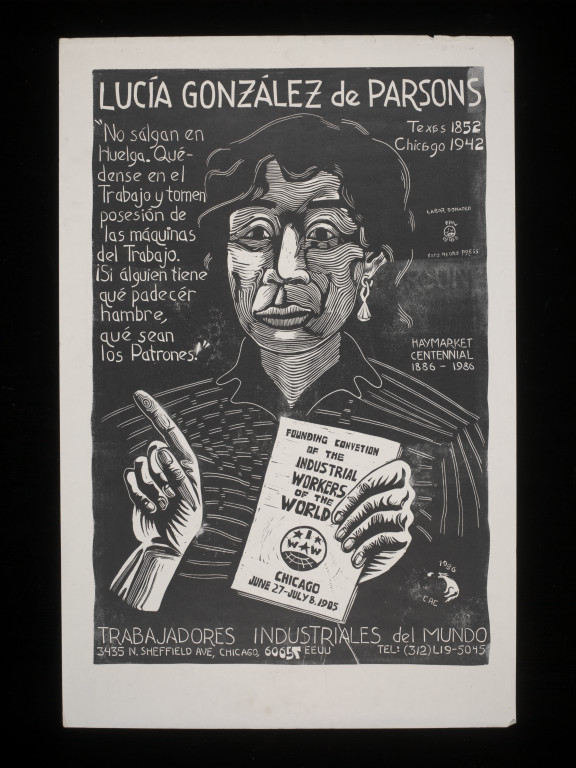

“Looking at State Violence: Lucy Parsons, José Martí, and Haymarket.” The [Oxford] Handbook of Nineteenth-Century American Literature. Edited by Russ Castronovo. London: Oxford University Press, 2012: 115-136.

This article investigates the influence of the expansion of mass-market visual culture in shaping literary meanings in the U.S.A. in the nineteenth century. It provides a transnational history of the Haymarket bombing and executions, and suggests that literary and cultural meanings in the late nineteenth century were crucially mediated and shaped by the expansion of the pictorial marketplace and the transformation of visual culture. The article discusses how José Martí and Lucy E. Parsons intervened in late-nineteenth-century practices of looking by reenvisioning iconic sentimental and sensational Haymarket scenes, and by raising questions about violence, the visual, and state power that connect world movements across space and time. Keywords: visual culture, literary meanings, U.S.A., Haymarket bombing, José Martí, Lucy E. Parsons, violence, state power

“Dime Novels and the Rise of Mass Market Genres.” The Cambridge History of the American Novel. Edited by Leonard Cassuto, Clare Virginia, Evy, and Benjamin Reiss. London: Cambridge University Press, 2011: 586-599.

This chapter traces a pre-history of the dime novel in the popular sentimental and sensational literature of the late 1840s and 1850s. It presents the proliferation of the dime novels introduced by Beadle and Company in the 1860s and 1870s. In 1860, Erastus and Irwin Beadle issued the very first dime novel, Ann Stephens's Malaeska; The Indian Wife of the White Hunter. Mary Andrews Denison's dime novels remind people of women's significant participation in the new culture industry and of the permeability of the boundary between sensational literature and the culture of sentiment in the early period of dime novel production. Many female authors of Beadle's dime Westerns focused on white settlers like Ann Stephens's Esther: A Story of the Oregon Trail. Finally, the chapter examines the dime novel's twilight era around the turn of the century, when it both competed with and inspired early cinema, comics, and pulp magazines.

“Popular, Mass, and High Culture.” A Concise Companion to American Studies. Edited by John Carlos Rowe. London: Wiley Blackwell, 2010: 432-452.

"It is difficult to theorize popular, mass, and high cultures without considering the relationships among them. It is also important to remember that they are concepts rather than things. Each of the keywords that modify culture – popular, mass, and high – brings with it a cluster of meanings, questions, and problems that have been shaped by particular historical conditions, struggles, and debates... 'Popular culture' is the most capacious of the three categories, and in American Studies its usage has often depended upon a broader, anthropological sense of culture; it has also been a keyword in debates about the national-popular, especially in the Popular Front and Cold War eras. In more recent years, however, global flows of culture have pushed American Studies scholars to theorize the popular in new ways that move beyond national frameworks...."

“Multiculturalism and Forging New Canons,” Blackwell Companion to American Literature, ed. Paul Lauter. Blackwell. 2010. (110-121).

During the last few decades, multiculturalism has been a key and contested term in US literary studies. In the 1960s and 1970s, representatives of the new social movements questioned university offerings and curricula, pressed for new departments and programs, and criticized the claims to universality that were offered by champions of dominant literary canons. As a result... in the 1980s new canons, which included more women and people of color and which often depended upon different conceptions of the literary, began to emerge. While some cultural conservatives responded loudly and angrily to these changes by recasting them as threats to Western civilization and a common culture, others sought to defuse the perceived threat of multiculturalism by assimilating it to a more traditional melting pot ideal...."

“June 1846: James Russell Lowell’s Biglow Papers are cut from the newspaper and pasted onto workshop walls all over Boston.” A New Literary History of America. Edited by Werner Sollors and Greil Marcus, eds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009: 263-68.

"Written in Yankee dialect, [Lowell's] poem, which was published a month after the US-Mexico War began, was an effort to voice antiwar and antislavery arguments in the idiom of a white workingman." In this essay, I situate the Biglow Papers in relation to the large body of popular newspaper writing and novels that focused on the war in the wake of the print revolution of the 1840s. When this popular literature is remembered at all, it is usually mischaracterized as an utterly jingoistic body of writing that spoke in one voice in support of the war. But although some of this literature advocated war and empire-building, many writers objected to it, often in language that resonated with that of Lowell's Yankee.

“Labor, Memory, and the Boundaries of Print Culture: From Haymarket to the Mexican Revolution.” American Literary History, Volume 19, No. 2, Summer 2007: 406-433.

This article is a very early set of reflections on how memories of the Haymarket anarchists shaped transnational social movements in the era of the Russian and Mexican Revolutions. Read it here.

“Sensational Fiction,” A Companion to American Fiction, 1780-1865, ed. Shirley Samuels. London: Blackwell, 2004: 179-190.

This piece situates sensational fiction in relation to critical discussion that emerged in the 1990s, along with work in allied fields such as theater and film studies, labor history, ethnic and cultural studies, and sexuality and gender studies, that made “sensation” a key word for scholars of nineteenth-century US literature..

“American Sensations: Empire, Amnesia, and the US-Mexican War,” American Literary History 13:1 (Spring 2001): 1-40.

The print revolution of the late 1830s and 1840s, which made it possible to reproduce and distribute newspapers and books at cheaper prices and in larger quantities than ever before, directly preceded the US-Mexico war. During the war, formulations of a fictive, unifying, Anglo-Saxon American national identity were disseminated in sensational newspapers, songbooks, novelettes, story papers, and other cheap reading material. But the existence of such a unified US national identity was anything but self-evident during this period, for the 1840s were also marked by increasing sectionalism, struggles over slavery, the formation of an urban industrial working class, and nativist hatred directed at the new, mostly German and Irish, immigrants whose numbers increased rapidly after 1845..Read it here.